pages/default.php (page)

Background & Approach

Some introductory history and the rationale underlying the site's organization

Context

Science has made enormous progress in understanding how the world works by breaking it apart: looking at the world in greater and greater detail and, through rigorous experimentation using the scientific method, seeing how these fundamental pieces interact in consistent ways. The result has been a wealth of knowledge regarding how many parts of our world operate.

But some systems do not lend themselves to being explored in this way. If we try to break them apart - isolating their components in order to analyze them - we wind up losing many of the properties we had set out to understand. These systems do not operate through straightforward mechanisms of linear cause and effect, and their behaviors cannot easily be replicated in controlled settings. As scientists began to look at these entangled systems, they realized that many such systems exist across different disciplinary domains - biological, economic, physical, and social. Complexity is a way to look at this other kind of system. While still a nascent field, we are learning more and more about these systems: the nature of their dynamics and the characteristics that bind them.

Overview

Flocks of birds; the fluctuations of the stock market; the structure of the internet: what do such systems have in common? While seemingly very different, over time we have identified that certain kinds of systems are governed by dynamics that are shared. While made of disparate parts, they can operate as a unity. While there is no central control, there is nonetheless distributed coordination. While made of individual components, the system is not simply the sum of its parts.

The concepts we associate with CAS were outlined as early as 1962 by Herbert Simon who, while not explicitly using the phrase 'complex adaptive' characterized certain kinds of systems as possessing both 'complexity' and 'adaptiveness'. The use of the phrase ‘Complex Adaptive Systems’ or 'CAS', can be traced back to the mid-1980s and the newly formed Santa Fe Institute. A think tank for advancing our knowledge of such systems, in 1986 the Institute announced a workshop on ‘Complex Adaptive Systems’ which were described as, ‘systems comprising large numbers of coupled elements the properties of which are modifiable as a result of environmental interactions’.

As we enter the mid-1980s both Santa Fe institute leaders John Holland and Murray Gell-Mann, began to refer to CAS regularly. That said, no specific definitions of such systems appear to be circulated until the early 1990s. From that point onwards, various description of CAS appear that outline its various ‘principles’, ‘attributes’ or ‘defining features’. To structure this website, we consider the similarities and differences amongst these.

Selection of Governing Principles

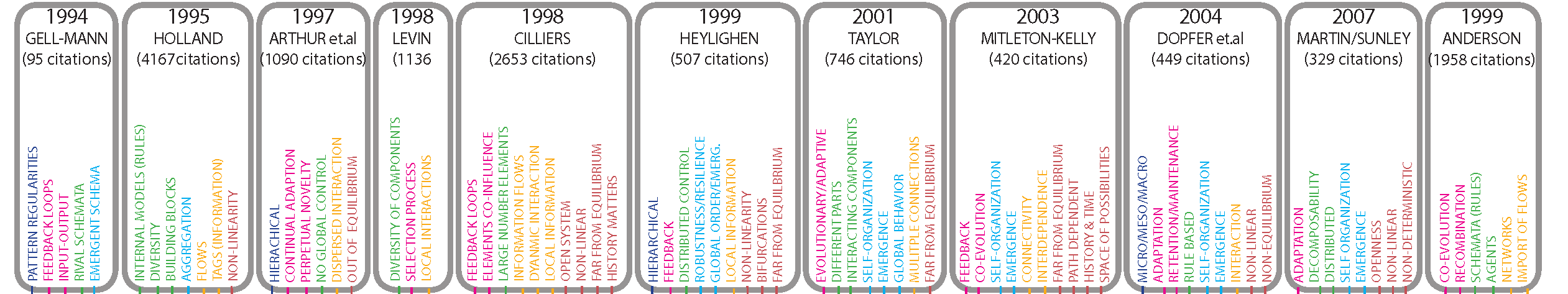

Of the descriptions of complexity circulated since the 1990s, this site considers eleven highly cited references as starting points:

(zoom in to see the lists - color coded to identify parallel principles that have been parsed)

While the overlaps between definitions are not perfect, the relationships between recurrent terms and ideas are consistent enough that we can draw out similarities. Thus, through analyzing the overlaps amongst these definitions we can generate a list of complexity's core GOVERNING FEATURES which include:

- bottom-up agents (associated terms in green);

- adaptive processes (associated terms in pink);

- information flows (associated terms in orange);

- non-linearity (associated terms in brown)

- nested scales (associated terms in purple); and

- emergence (associated terms in blue).

These features of complex systems provide useful starting points from which to examine other key concepts, thinkers, and terminology associated with the field. Further, identifying these features can help us understand why some researchers engaging with complex systems thinking might find it difficult to relate to others from different discourses that also embrace complexity.

Uncluttering the ambiguities:

This site aims to give greater clarity to an emerging field that remains somewhat ambiguous in its knowledge domain. In his survey of complexity theory, philosopher Paul Cilliers comments, ‘the concept remains elusive at both the qualitative and quantitative levels’. Complexity theorist Francis Heylighen echoes this sentiment, stating:

'Qualitative descriptions can be short and vague, such as ‘complexity is situated in between order and disorder’. More commonly, authors trying to characterize complex systems just provide extensive lists or tables of properties that complex systems have and that distinguish them from simple system. These include items such as: many components or agents, local interactions, non-linear dynamics, emergent properties, self-organization, multiple feedback loops, multiple levels, adapting to its environment, etc. The problem here of course is that the different lists partly overlap, partly differ, and that there is no agreement on what should be included.'

These disagreements result in considerable ambiguities in how concepts are discussed. Different CAS discourses employ descriptors that, while intending to describe the same features, use completely different terms. Hence, an ever-increasing array of terms and concepts - words or phrases like Manifold, Phase Space, ‘Affordances’, and The Virtual - all allude to similar concepts related to complexity, but nonetheless appear foreign to those operating from different conceptual domains.

Even the differences between central concepts like Emergence and Self-Organization are unclear and, while some researchers try to solve these ambiguities by referencing mathematical properties (such as information content) or making distinctions between algorithmic, deterministic, and aggregate complexity, such technical distinctions raise more questions then answers for those coming from the social sciences.

Of course, conceptual clarity is not always necessary. It is certainly possible to employ CAS terminology in looser, more metaphoric ways – with 'choices' becoming ‘Bifurcations’ (regardless of whether or not this is a threshold associated with a relevant control parameter) - and complexity being equated complicated (whether or nor we are referring to a non-linear system). That said, such usages make it increasingly difficult to gain insights across discourses.

Does this matter? If we are to gain insights from complexity theory, it would be helpful to have a common understanding of what we are talking about, and learn from each other across domains.

so...Start Navigating Complexity

Photo Credit and Caption: BBC

Cite this page:

Wohl, S. (2022, 23 May). Background & Approach. Retrieved from https://kapalicarsi.wittmeyer.io/history

Background & Approach was updated May 23rd, 2022.

Nothing over here yet

Navigating Complexity © 2015-2025 Sharon Wohl, all rights reserved. Developed by Sean Wittmeyer

Sign In (SSO) | Sign In

Related (this page):

Section:

Non-Linearity Related (same section): Related (all): Urban Modeling (11, fields), Resilient Urbanism (14, fields), Relational Geography (19, fields), Landscape Urbanism (15, fields), Evolutionary Geography (12, fields), Communicative Planning (18, fields), Assemblage Geography (20, fields), Tipping Points (218, concepts), Path Dependency (93, concepts), Far From Equilibrium (212, concepts),

Nested Orders Related (same section): Related (all): Urban Modeling (11, fields), Urban Informalities (16, fields), Resilient Urbanism (14, fields), Self-Organized Criticality (64, concepts), Scale-Free (217, concepts), Power Laws (66, concepts),

Emergence Related (same section): Related (all): Urban Modeling (11, fields), Urban Informalities (16, fields), Urban Datascapes (28, fields), Incremental Urbanism (13, fields), Evolutionary Geography (12, fields), Communicative Planning (18, fields), Assemblage Geography (20, fields), Self-Organization (214, concepts), Fitness (59, concepts), Attractor States (72, concepts),

Driving Flows Related (same section): Related (all): Urban Datascapes (28, fields), Tactical Urbanism (17, fields), Relational Geography (19, fields), Parametric Urbanism (10, fields), Landscape Urbanism (15, fields), Evolutionary Geography (12, fields), Communicative Planning (18, fields), Assemblage Geography (20, fields), Open / Dissipative (84, concepts), Networks (75, concepts), Information (73, concepts),

Bottom-up Agents Related (same section): Related (all): Urban Modeling (11, fields), Urban Informalities (16, fields), Resilient Urbanism (14, fields), Parametric Urbanism (10, fields), Incremental Urbanism (13, fields), Evolutionary Geography (12, fields), Communicative Planning (18, fields), Rules (213, concepts), Iterations (56, concepts),

Adaptive Capacity Related (same section): Related (all): Urban Modeling (11, fields), Urban Informalities (16, fields), Tactical Urbanism (17, fields), Parametric Urbanism (10, fields), Landscape Urbanism (15, fields), Incremental Urbanism (13, fields), Evolutionary Geography (12, fields), Feedback (88, concepts), Degrees of Freedom (78, concepts),